A Tough Reclusive Mother - Palpating the Cranial Dura Mater (Part 1)

- Michael Hamm

- Oct 9, 2013

- 6 min read

Note: This is a two-part ‘how-to’ article. Part 1 focuses on anatomy and mechanics; Part 2 gives some methods of application.

Imagine placing your hands on the above head, and engaging the outer tissues in such a way as to transmit force to the membrane shown in yellow. Imagine that doing so with skill and intention can lead to positive physiologic change. Those are the two basic premises of dural contact in bodywork.

We’ll skip for now a discussion of why you might want to do this, and what physiologic changes it may induce. We’ll also duck questions on craniosacral work and cranial osteopathy, because both are cluttered with concepts unhelpful for a grounded discussion. We will try to make only reasonable assumptions.

The first thing we need for effective dural palpation is to imagine the body from the Dura’s perspective.

The Inmost Skin

The Dura Mater is a fascial membrane that encloses our central nervous system, and continues as nerve sheaths to every corner of the body. It hangs suspended, tugged in all directions, inside our cranium and spinal canal.

We could call it the deepest fascial tissue, since it lies housed within the embryonic midline. All other fascia migrates outward as the embryo grows, but the Dura (once you can call it that) stays put. Its fidelity to midline wins the Dura a great deal of protection — a strong bony sheath and a thick muscular envelope. The only problem, because of its connectedness and centrality, is that it constantly must adjust to the movements of long limbs, floppy necks, and twisting spines.

Does it care? Has the Dura any need of mechanical health? Is this ‘tough mother’ really so uptight? Like all ivory tower-dwellers, the Dura can be prone to strong reactions. It’s not always inflamed or hypersensitive, but when it is, whoo boy. The body takes great pains to avoid its ire. (For background on this, ask the Australian PTs. In fact, just ask them about everything.)

One thing shared by every nervous system is the remarkable degree to which other tissues protect it. Bones and fasciae turn direct forces into harmless obliquities. Layered fluid chambers convert loud vibrations to gentle murmurs. Blood vessels are grasped and filtered by glial cells. And muscles constantly limit their own length based on a neuro-protective policy.

But don’t take my word for it: Try sinking into a gentle hamstring stretch. Keep a neutral back and a long spine, with your eyes pointing down. Stop when you encounter the first resistance. Now, extend your head to look forward. You just fed dural slack into your spinal column — does the hamstring allow a deeper bend?

This is the world as seen by the Dura. Cradled, bathed, actively protected, it constantly shifts within the body’s lumbering expanse, tasked with protecting the most fragile of all organs. One could understand why it might get starved for attention.

Dura as a Water Balloon

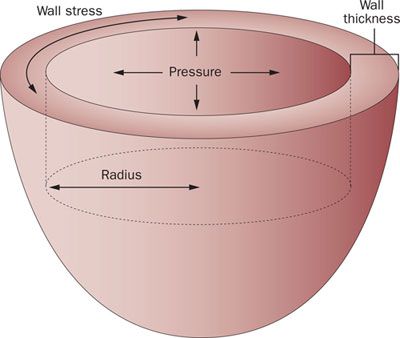

No fascial tissue can really be understood without fluid pressure in the picture. This is the case with Dura, against whose interior the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pushes outward at 2-3 kiloPascal. (Note: 1 kPa roughly equals 1 standard water balloon.)

Why would the body maintain such a pressurization? Because the stiff competition between CSF and Dura accomplishes a fantastic evolutionary feat: Our delicate sopping hulk of a brain, which normally weighs 1300 grams is reduced to 50. Fluid and fascia also create a pressure-tension buffer, which neutralizes vibrations and impact force.

When you think about it, a water balloon displays a form of tensegrity. Its integrity based on the dynamic balance between opposed forces of tension and compression. In a classic tensegrity model, dowels represent compression members and bungee cords represent tension members. Squash this dowel-and-bungee model, and it springs back into shape. Distort one corner of it, and the whole structure adjusts to find a new balance. Bodyworkers (like the inimitable Tom Myers) have long used these models to describe the mechanical relationship of bones to the fascial matrix.

But the same behavior can also be seen in fascial fluid chambers. Instead of dowels, they have compartmental fluid pressure. Instead of bungee cords, it’s membranes under tension — call it ‘Planar’ or ‘Fluid’ tensegrity. Everything from single cells to muscles to dural balloons display these same properties — elastic memory and systemic re-balancing.

Look back at that yellow line at the top of the page. Imagine resting your finger pads gently on the outer surface, and directing a light inward pressure through the bone. The bone resists you, of course — but is it only bone? Or can you feel the dural balloon on the bone’s interior?

You might be thinking, “Waaaaaaait a minute. How does one feel through bone?” Good question.

Do Cranial Bones Move When Pressed On?

It depends on what you mean. The cranium, like all bone tissue, can deform: the question is how much, and whether it can be felt. It turns out, as you’ll see next week, that Dura can plausibly be contacted even if the cranium has no movement whatsoever. But we must pause here to acknowledge a chasm of disagreement in the bodywork world: the (non-)debate over cranial mobility.

Many skilled practitioners claim to feel the skull move — both passively and actively — and can describe this movement in exquisite detail. Skeptics insist with incredulity that such movement isn’t possible and hasn’t been measured convincingly. Both arguments have now ossified to the point where any real learning is tragically deflected.

If you find yourself with a strong opinion on this matter, I don’t intend to change it. But I have a suggestion on how you deploy your perspective:

• Practitioners: Make room for the possibility that what you’re feeling isn’t really there.

• Skeptics: Allow that what is felt may be clinically meaningful.

If you’re capable of these, then you maintain the ability to learn things, both in treatment and in conversation. I will proceed in this post to tell you what I feel when I intend dural palpation, and what models have helped me make sense of what I’m feeling.

Springy Within a Small Range

Bones, like tree branches and antlers, are semi-elastic composites. Their collagen fibers are spooled around a crystalline ground substance that efficiently diffuses force over a wide area. But do cranial bones have an elastic range that allows palpable deformation? Can the cranium really deform enough for you to ‘hook’ the dural membranes? From extensive research, I would call it unlikely but not out of the question. But in practice, this is exactly what it feels like.

It’s not hard to demonstrate the feeling: Put your right forearm in a handshake position. Then with your left hand, gently contact the midpoint of your forearm: thumb on bottom, fingers on top. Let your finger pads float in the spongy skin layer, and position them above the shafts of ulna and radius. Now slowly sink, until you’ve just barely felt the smooth contour of bone. This is your starting depth. Now try gradually compressing the bones toward each other, feeling the ulna and radius bend inward, then rise back to starting depth. Try it again, even slower.

You may notice that the bones bend a little. The first half-millimeter or so is actually pretty easy. Then the bones begin to resist, and then they yield not at all. You are seeing the springy behavior of bone, which varies widely depending on bone in question. But all bones seem to follow the general contours of Hooke’s Law:

F = (K) X

(where F is force, K is a ‘spring constant’ , and X is the degree of deformation.)

In the above exercise, you squeezed your forearm (F), and the bones yielded a bit (X), and thus revealed their springiness (K). For now, just see that your subjective experience was mirrored by some physics: For small deformations (low X), you don’t need much force. But bigger deformations require increasingly more force. This is a key functional property of bone tissue: to yield just a little bit, but then to resist mightily.

Most bones are stiffer than the ulna/radius, so you should expect smaller deformations in a temporal or frontal bone. But in my daily experience as a bodyworker, the exact same behavior is felt in the cranium. It feels neither subtle nor mysterious. I have read every skeptical article I can find… and yet it moves.

Not only that, but the movement of the cranium seems directly transmissible to the dural membranes. I find it possible to feel a wide range of tension patterns in the Dura, and then treat them effectively, when applying a gentle force to the surface of the head. If I apply it too quickly, or with too much force, the sensation disappears.

Does that sound weird? It sure does to me. Tune in next week for Part 2, where we explore some hands-on techniques.

Commentaires