Blades of Glory: Navigating the Scapular Neurofascia

- Michael Hamm

- Sep 7, 2013

- 6 min read

NOTE: This post focuses on the location, palpation, and mechanical environment of nerves and their fasciae. The physiology of nerve entrapment and specific diagnostic/assessment criteria are not covered here.

“I always get pain right here“, says your patient, pointing vaguely to their shoulder blade. They say it with diagnostic emphasis, but you don’t share their enthusiasm. It’s the fourth patient today to confess such discomfort, and, judging from the abundance of persons curled around laptops and steering wheels, you’re likely to keep seeing folks with shoulder blade problems. You could be forgiven for blurring each case together, or wondering if your ministrations can create lasting change.

But the commonality of shoulder blade problems shouldn’t lead us to treat all sufferers the same, nor should we shrink from the challenge of creating long-term improvement. We use our shoulder blades constantly, in all kinds of ways, and so it’s not surprising that multiple schools of emphasis have arisen to explain scapular pain and dysfunction. The dominant models are something like these:

— Muscle-centric (“Tight pecs, overstretched rhomboids”),

— Bone-joint centric (“Rib Head dysfunction”), or

— Function-centric (“Improper stabilization/activation”).

None of these models are exclusive of each other… in fact I recommend gaining familiarity with each. But they each have blind spots, and when these modes of reasoning fail you, I urge you to consider the neurofascial tissues surrounding the shoulder blades as your primary object of inquiry.

THINKING OUTWARD FROM DURA

You can’t connect a local neural tension pattern to the whole system unless you can visualize what the spinal dura mater is experiencing. This may be fine if your patient has plenty of slack in their system. But what if one or both sciatic nerves are under tension? What about that old L4 disc herniation? That kidney surgery? That contralateral C1-C2 fixation? Make at least a cursory assessment of midline tension — whether it’s excessive, and where it’s coming from — before zooming into the local area. (NOTE: I plan to cover specific methods of midline assessment in later posts.)

From the scapula to the dura, the primary vector of mechanical tension is through the upper and posterior brachial plexus. Because mid-cervical nerve roots (unlike their thoracic and lumbar cousins) have small ligamentous tethers to their exiting transverse foramina, neural tension at the brachial plexus can exert unusually strong influence on vertebral position. So if you’re noticing a tendency of C5 and C6 to laterally deviate or rotate, check out the scapular neurofascia on the same side.

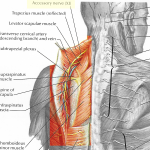

SUPERFICIAL NERVES

Before dropping into familiar muscles and bones of the shoulder blade, assess the mobility and sensitivity of skin. Branching in the subcutaneous fascia, and anchored down to the first layer of deep fascia, are a host of cutaneous nerves. When inflamed, these superficial nerves can generate pain, fascial restriction, and reflexive holding. (As a fun experiment, try working onlythis surface layer, and do a before-after assessment of scapular mobility.)

Supraclavicular nerves (C3-C4)

Spilling over the collarbone in front, and anchored to the acromion and lateral spine of the scapula, are these spindly branching fibers from the cervical plexus.They can be palpated as hard filaments on the surface of the clavicular and acromial periosteum.

C5-T7 Dorsal Rami (medial branch)

These emerge posteriorly from the nerve roots, perforate through the paraspinal compartments and the spine-attached scapular muscles, and then join the surface layer about 1 cm lateral to the spinous processes. From there they travel laterally and inferiorly, roughly along with classic dermatomes. (Warning when looking at dermatome maps: skin innervation is highly irregular and redundant.) These dorsal rami can become irritated at the nerve root (e.g. rib head subluxation), at their perforations, or where they cross over the scapula. Sometimes a winging scapula’s medial border can “rake” these nerves from below, and cause them to inflame locally.

Spinal Accessory Nerve (Cranial XI)

A strange hybrid, this nerve sidles up to the spinal cord within the cervical spinal canal, gathering itself from the C1-C5 rootlets, climbing into the cranial base, and then exiting through the jugular foramen. (For this reason, don’t ignore the cervical dura when treating this nerve). From its exit, the Accessory nerve splits into an SCM division (anteriorly) and a Trapezius division (posteriorly).

It can be palpated along the length of Trapezius on its underside, feeling like a squiggly branching vine, whose main trunk is about 1 cm medial to the medial border of the scapula. As with the dorsal rami, this nerve can become irritated by excessive winging of the scapula, and likewise by scapular protraction/anterior tilt.

NERVES ANCHORED IN THE SCAPULA

The nerves here become more challenging to palpate, because they lack the transparency of surface nerves. But don’t give up! Sink to carefully to the appropriate layer and look for gummy thickenings in between layers of muscle/fascia. These will be much more obvious when inflamed, and they respond well to gentle mobilization.

Dorsal Scapular Nerve(C5): This frequent culprit jumps off the superior edge of the brachial plexus, hitches itself to the lateral underside of levator scapulae, and then threads itself slyly into the bellies of levator and rhomboid minor and major. Its main trunk can be palpated with relative ease just deep/anterior to levator’s attachment at the superior angle. With practice, it can also be felt just deep to the rhomboid layer, just lateral to the medial border. (It will still move with the scapula during passive ROM.)

Suprascapular Nerve (C5-C6): This rotator-cuff nerve also begins at the superior brachial plexus — just ~2 cm more distally. From there it deftly tunnels posteriorly into the supraspinatus muscle, through a narrow hole at the suprascapular notch. Once through supraspinatus, it snakes around the lateral edge of the spine of the scapula, spreads into the belly of infraspinatus, and also sends a branch to the lateral/superior glenohumeral joint.

The suprascapular nerve is especially vulnerable at the suprascapular notch: If chronically downwardly rotated, the scapula can keep the nerve irritated from excess tension. In cases of supraspinatus muscle strain, the nerve can experience sudden shearing (and sometimes partial denervation) at the interface of muscle and notch. However, this vulnerability also lends us a good treatment site: gentle nerve release just anterior to the suprascapular notch can bring surprising amounts of relief.

The Subscapular ‘Trio’: For ease of remembrance, I group together the trio Upper Subscapular (C5-C6), Thoracodorsal (C6-C7-C8), and Lower Subscapular (C5-C6) nerves. As a group, they peel off the middle Brachial plexus, posterior cord, and join into the anterior fascia of subscapularis. Respectively they innervate the subscapularis, latissimus dorsi, and teres major. These are often irritated when a protracted and/or depressed scapula rubs them against the upper ribs.

They can be palpated via a standard approach to subscap: Get your finger pads on the anterior scapula, and feel along the smooth epimysium until, at the central muscle belly, the fascia becomes gummy and tacked down. This is the fascial envelope that contains this trio, and they will often thank you for applying moderate static pressure or shearing fascial release.

Axillary Nerve (C5-C6)

Oft-forgotten but frequently cranky is this tightly wound nerve, which also originates at the posterior cord of the Brachial Plexus, briefly joins with the Subscap fascia, and then perforates posteriorly just below the humeral head and just above the tendon of teres major/lattisimus dorsi. From there it sends a small shoot to the Teres Minor while its main branch curls around the humeral head, innervating both deltoid and the inferior-lateral glenohumeral joint.

This joint innervation is key, because I’ve found Axillary nerve to be strongly implicated in early-stage Frozen Shoulder, and also more conventional shoulder impingement conditions. The combination of scapular depression, downward rotation, and humeral medial rotation (AKA ‘Roller bag posture’) is a perfect recipe for generating chronic inflammation in this nerve.

To find this nerve proximal to the humerus, you can slide distally along the anterior Subscap. You will find a thick, tender spot at the Subscap’s musculo-tendinous junction, where the Axillary nerve ducks under toward the glenohumeral joint. On the posterior side, follow the long head of triceps all the way to its attachment at the infraglenoid tubercle. Then pivot your fingers posteriorly, nudging aside the belly of deltoid and find the nerve embedded there inside a thick fascial envelope.

ALSO WORTH MENTIONING:

Though not directly joined with the scapula, the entire Brachial Plexus, and especially posterior branches like Radial and Long Thoracic nerves, can influence — and be influenced by — scapular motion. This is why it’s good to begin and end with zoomed-out inquiries, so that your newly found specificity does not miss the obvious larger pattern.

This post is predicated on the idea that, with a decent map and some patience, you can learn to visualize and feel these structures in practice. And, when combined with good clinical strategies… that you can treat them effectively. Happy neurofascial navigation!

Comments