Seeing Past the Wound Man

- Michael Hamm

- Feb 2, 2012

- 4 min read

As we in the bodywork world begin to nerd out on a science literature that, for the first time, is being conducted with a knowledge of how we work, it’s important to ask how the onslaught of relevant information affects our treatment sessions. So let’s take a look at another information revolution in medicine: the wound man.

Medicine in medieval Europe was no joke. Anesthesia, sanitation, antibiotics, and plain old soap were yet to be invented, and folks were no strangers to gruesome calamity. Knowledge of anatomy was scarce, experiential, and inaccurate. Medical texts were expensive to reproduce. In the case of treating an acute wound, you had to move quickly. Doctors needed a compact guide for a whole variety of wounds. And so emerged this very clever tool of medical texts.

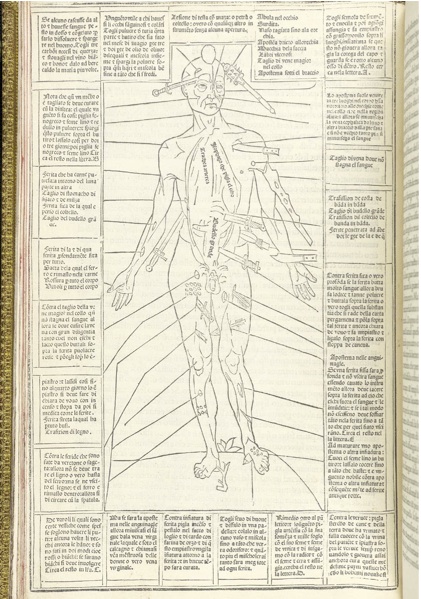

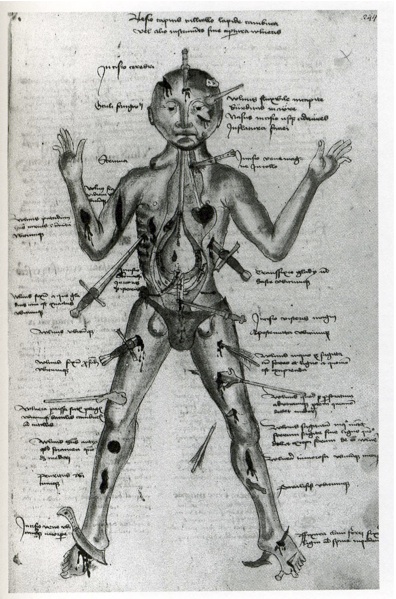

Wound men are composites of medical information, showing human frames with a christmas tree’s worth of gory insult. On a single page you find this unlucky guy, staring outward, gamely displaying a dagger in his ribs, a barbed arrow through his thigh, a cleaver to his foot, and twenty other hacks and stabs. Adjacent to each wound is a short block of text that communicates the essentials of treatment. For all this rude specificity, it was a brilliant invention: a cheat-sheet for the doctor on the move. It wasn’t pretty, but it worked.

Cool, right? And thank goodness for modernity! Medicine is now a more friendly enterprise, as practitioners strive for better patient care, more precise methods, and more accurate diagnoses. Our training books are thick, and our information resources are effectively boundless. We don’t memorize short blocks of text but entire chapters. We no longer turn the textbook page to see these wound men, suffering so stoically.

But are we really rid of them, or do they persist in our minds? Think of diagnostic trees or muscle testing charts – we still try to imagine all possible problems before we investigate a patient’s body. The danger with such thinking is that it’s easy to disconnect from the whole person standing in front of you. Instead of a mostly healthy, mostly vital human being, the healer sees a wound man: a collection of potential pathologies to be whittled down to the right one.

Bodyworkers and other holistic practitioners have a special interest in staying connected with the totality of someone. We work in close collaboration with an internal healing force, and when we stop listening carefully to the body, we become useless. So we pride ourselves in treating the whole person: our sessions are longer, our treatment rooms are disarmingly cozy, and in our examination we tend to look for systemic patterns.

But we are not free of wound men, either. We see someone enter our room with a limp, and our minds fire off with a rush of possibilities. (Foot / Ankle / Knee / Hip?) (Acute / Subacute / Chronic?) (Bone / Ligament / Muscle / Nerve?) With practice, we can spot deviations, compensations, and limitations in our patient. We begin to feel powerful in our assessment techniques, and these assessments often lead to better treatment. Our patients are quite happy to hear a coherent story for why they are suffering — “Oh, so it’s my psoas? Good to know.”

Deductive reasoning like this is essential for clinical bodyworkers, but it’s equally essential that we transcend it. If all we see are broken things to be fixed, then we end up being glorified mechanics. Patients leave our offices feeling comforted by information, but also hopelessly fragmented by it. Their intake forms become a breathless litany of things wrong with them: “Oh man, where to begin — my back is all messed up, my neck is out of alignment, my legs are the wrong length.” Et cetera.

Even those bodyworkers using energetic, somatic, and shamanic methods are not immune. They may fixate on more esoteric problems — the stagnation of Qi or the imprint of trauma – but they can fixate nonetheless. And the effect is the same: patients learn to view their bodies as malfunctional, untrustworthy, and dumb.

No matter what the model is that you apply, it’s still a trap if it’s all you see. And that’s a shame, because it severely limits the potential healing in bodywork. Once we’ve made a session plan, it’s important to shake off the wound man. If we friction some scar tissue on a cervical facet joint, can we also awaken a sense of strength in that neck? When we treat misalignments, does our patient know what balance feels like?

This higher-order treatment requires us to do some things – make space, sit still, ask questions – that don’t seem exactly like treatment. We may feel duty-bound to fill every moment of a session with some move or some intervention, lest we waste precious time and money. But in fact the opposite is true: we are duty-bound to pause, to be curious, and to get out of the way.

If we attend only to fixing problems, then we have taken our eyes off the prize: transforming a patient’s relationship to suffering. And really, if that’s not your ultimate goal, what’s the point?

Comments